| Neutrality of Cash Flow Taxes WAYNE MAYO |

This paper is a shortened version of the paper 'Rent Royalties' by Wayne Mayo publised in the Economic Record in September 1979. The shortening mainly involves removal of discussion of neutral income taxation arrangements, discussion which is better handled in Wayne Mayo's 2011 book Taxing Investment Income, as well as discussion of the interaction between cash flow royalties and income taxation, which is again better handled in Wayne Mayo's 2013 book Taxing Resource Rent. Additional points of clarification and refinement are made throughout this version, particularly in relation to discount rates for assessing project viability and associated Resource Rent Tax threshold rates. Simulations of the effects of cash flow taxes on investment projects, in the presence of income taxation if desired, can be undertaken by the MyProject computer package.

Analysis and discussion in this paper is refined, broadened and deepened in Wayne Mayo's 2013 book Taxing Resource Rent

On neutrality grounds, royalties designed to tax only the economic rent of mining or petroleum operations - 'rent royalties' - are preferable to royalty schemes currently used in Australia. In contrast to the ideal rent royalty in the form of a Brown Tax, the Resource Rent type of royalty generally has an asymmetrical effect on the probability distribution of the internal rate of return or net present value of projects being considered for investment. Despite this asymmetrical effect, with appropriate design and selection of operating parameters, this royalty scheme may not greatly affect the screening of projects for investment purposes.

A Musgravian separation of efficiency and equity effects - Musgrave (1959, Chapter 1) - is useful when considering a move to import parity pricing of energy products. However, in practice the two effects cannot be separated: a policy of import parity pricing designed to improve the allocation of resources will always have equity side effects. Further, a policy aimed at changing the equity effects of such a pricing policy may itself have associated efficiency effects.

The policy in Australia of moving from below world prices of domestically-produced crude oil to import parity has been implemented primarily on efficiency grounds. Nevertheless, a redistribution of income from previously subsidized consumers to crude oil producers is one obvious equity side effect of this policy. It may appear that this resulting redistribution of incomes only involves equity effects, and thus best left to government for consideration. However, if government decides to redistribute the gains from domestic crude oil production by imposing royalties, the method by which these royalties are imposed can adversely affect efficient resource allocation. The royalties ideally should be levied so as not to affect investment decisions after income tax.

Discounted cash flow techniques are often used as the initial screening process to identify potentially viable investment projects. The two measures most commonly used are discounted net present value and internal rate of return. The ideal royalty scheme should not affect either the screening of potential investments nor the ranking of these with regard to expected profitability. The theory of schemes for taxing economic rent which are neutral regarding investment-screening decisions can be used to design such a royalty scheme which can then be compared to the currently used royalty schemes regarding investment neutrality.

The two neutral rent-tax schemes which will be considered here are the Brown Tax and the practical version of this tax, the Resource Rent Tax. Two comparisons form the main body of the paper: comparison of the Brown Tax and the Resource Rent Tax; and the comparison of current royalties imposed on mining and petroleum operations with either the Brown Tax or the Resource Rent Tax applied before or after company tax. Discussion of the detailed practical issues associated with implementation of a Resource Rent type of scheme are outside the scope of the paper.

Discounting the stream of expected net capital expenditures and net receipts of a project at its before tax internal rate of return on total investments (that is, excluding all cash flows relating to the financing of expenditures) results in the following equality:

Brown (1948, pgs 309-310) shows that applying a tax scheme, which incorporates immediate expensing of all capital expenditure and full loss offset, to the same stream of capital expenditures and receipts results in the discounted equality (with discounting at the same pre-tax internal rate of return):

The Brown Tax would also remain neutral if investment screening was based on the discounted net present value criterion. Equation (1) can be expressed more generally to show the net present value before tax, NPVb, when using any discount rate (with internal rate of return being the discount rate at which NPV equals zero). That is,

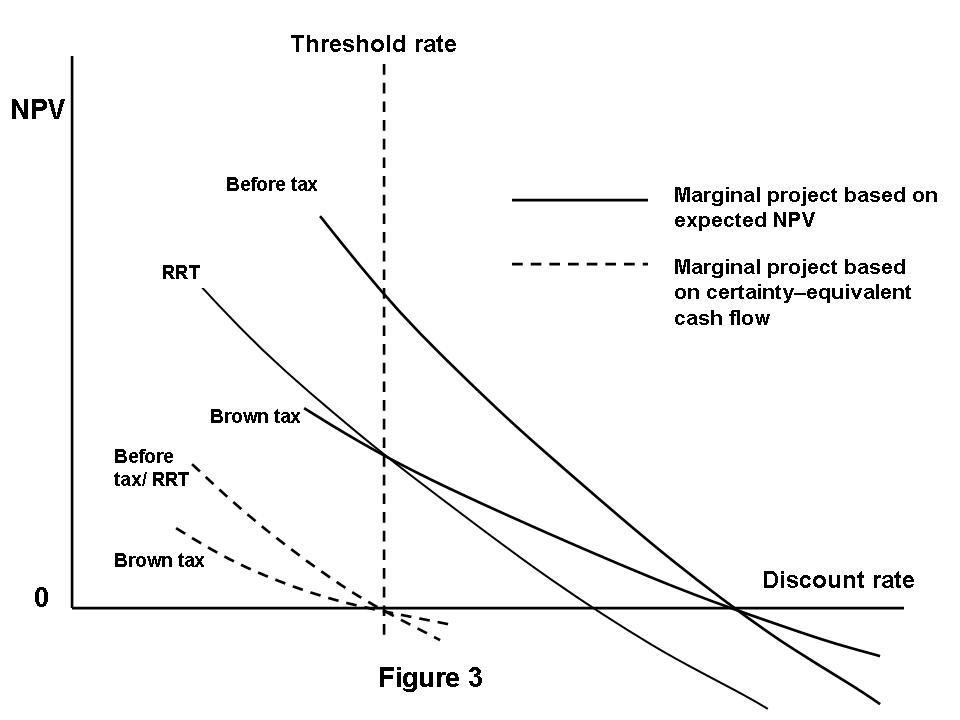

The relation between the discounted NPV curve of a project before and after the Brown Tax (with a 0.5 tax rate) is shown in Figure 1. The figure shows the internal rate of return constant after the tax and the NPV reduced by 50 per cent at each discount rate.

When screening investment projects, entrepreneurs are not simply concerned with the internal rate of return or net present value determined from the expected (or forecast) cash flow of projects. The shape of probability distributions of internal rates of return or net present values showing the spread of possible outcomes of potential projects influences investment decisions, reflecting the effects of risk.

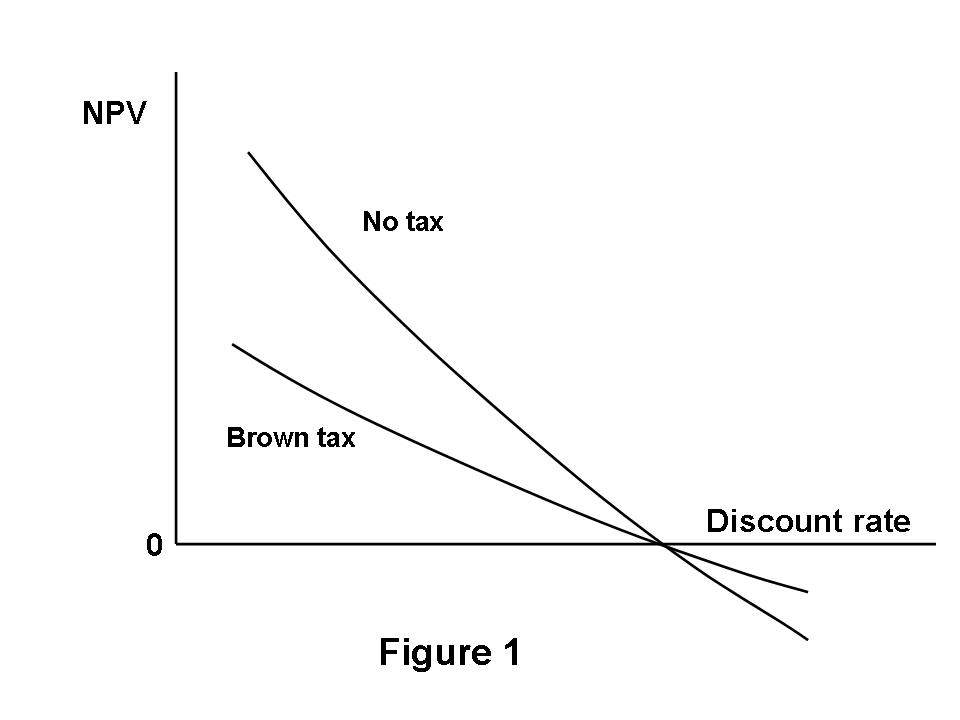

As the before-tax internal rate of return of any possible project outcome determined by a feasibility study is unaffected by the Brown Tax, the before-tax rate of return probability distribution of potential projects will also not be affected after tax. In contrast, the Brown Tax reduces the absolute value of each possible pre-tax positive or negative NPV of potential projects by a proportion equal to the tax rate. Consequently, the standard deviation (as well as the expected value) of each project's NPV probability distribution is reduced by this same proportion. Figure 2 illustrates the effect of the Brown Tax (with a 0.5 tax rate) on the NPV probability distribution of an investment project at the margin (only just considered viable) before tax. The pre- and post tax NPV probability distributions of a marginal project in Figure 2 are built up assuming the cash flows of each possible outcome are know with certainty and are therefore discounted using a risk-free discount rate (the riskless return that the entrepreneur could alternatively get from the financial market). Thus, the expected pre-tax NPV and post-tax NPV are greater than zero to balance the spread of possible NPV outcomes. Investment projects above this margin would include those with either higher expected net present values or with a lower spread of possible outcomes.

Again investment screening decisions based on consideration of the NPV probability distribution would not be affected by a Brown Tax applied economy wide. While the tax would reduce the expected NPV and the uncertainty associated with potential projects, these would be reduced by the same proportion for all projects (though the ranking of projects may be affected if entrepreneurs' trade-off between expected NPV and its associated variance is not linear). As the tax rate approached 1.0 the post-tax expected NPV and associated variance of all projects would approach zero - and the graph of the post-tax NPV in Figures 2 would approach a vertical straight line cutting the NPV axis at zero - representing a situation where negative annual cash flows are fully reimbursed and positive annual cash flows are fully appropriated. In Figure 1, a tax rate just less than 1.0 would result in a line almost touching the discount rate axis but still actually cutting the axis at the before-tax rate of return value. With tax rates less than 1.0, as Brown (1948, pg 310) notes, government could be viewed as making 'a capital contribution on new investment at the same rate at which it shared in future net receipts'.

Under this neutral tax scheme, the discount rate used by entrepreneurs to estimate NPV probability distributions of projects would be the same whether the estimation was carried out before or after tax. The discount rate is independent of the tax rate because the opportunity cost to entrepreneurs' of tying their money up in a project is the same after the tax as before. Thus, in building up NPV probability distributions, entrepreneurs would use a discount rate equal to the time preference rate of money. Projects would be evaluated and decisions made on the basis of NPV probability distributions built from the same risk-free discount rate and entrepreneurs' attitude to risk.

Rather than using the full NPV probability distribution, entrepreneurs may view a potential project's expected NPV based on the 'certainty equivalent' of the range of possible cash flow outcomes (or a single forecast or expected cash flow) in each year over the project's life. Thus, an entrepreneur might be prepared to exchange a forecast of $1000 for risky net receipts after one year and after two years for a certain $950 after one year and for a certain $890 of net receipts after two years (while not a general requirement, these numbers reflect risk increasing at an approximately constant rate). All the certainty-equivalent cash flows across a potential project's life would then be discounted at the risk-free rate to obtain the project's NPV and a marginal project would have a zero NPV. Similarly, a risk component could be incorporated into the discount rate in the determination of NPV based on the project's expected or forecast cash flow (the above two years of $1000 net receipts). In this case (which is commonly used in practice), the risk-inclusive discount rate might be considered as a proxy for the effect of a characteristic level of risk in the industry of the project under consideration. Using a risk-adjusted discount, however, suffers from more restrictive assumptions (notably, that risk is increasing at a constant rate year by year) which often may not suit mining and petroleum projects where the results of early exploration determines the future of the projects.

In the text, the distinction is made between the 'expected NPV' based on the complete NPV probability distribution built up using a risk-free discount rate and 'NPV based on certainty-equivalent cash flow', again using a risk-free discount rate. Thus, NPV in the equations in this paper can be taken to either represent: determination of NPV based on certainty-equivalent cash flow; a situation of certainty with regard to future cash flow; or but one NPV estimation out of all possible outcomes across a project's NPV probability distribution.

Pre-tax discount rates unchanged by the Brown Tax contrasts the situation with income taxation which incorporates interest payments and interest receipts in the tax base. With interest included in the tax base, the pre-tax discount rate is changed and with that change the treatment of capital expenditure required for neutrality changes from immediate write-off under the Brown Tax to annual change in value of assets created by capital expenditures under income taxation. This underlines the exclusion of cash flows associated with capital raisings and lending as a crucial design feature of the Brown Tax along with full loss offset and immediate expensing of capital expenditure.

A variant of the Brown Tax, which does not incorporate full loss offset with its associated cash rebates for negative annual cash flow, is the Resource Rent Tax (RRT). The RRT Scheme was proposed by Garnaut and Clunies Ross (1975) specifically for large natural resource projects that are supplied and financed from foreign sources. The discussion of the RRT is broadened by Garnaut and Clunies Ross (1979).

This scheme is equivalent to the Brown Tax Scheme except that if gross receipts are less than allowable deductions in any year, then the tax loss is carried forward with an added interest component per year (at a specified 'threshold' rate) to be offset against any future positive cash flows. This overcomes the requirement for government cash rebates for tax losses. Garnaut and Clunies Ross proposed that the threshold rate would ideally be set at a level considered to be equal to the risk-inclusive discount rate appropriate to the corresponding industry. This risk-inclusive discount rate might be viewed as a proxy for the effect of a characteristic level of risk, referred to earlier, for projects in a particular industry.

An alternative view, however, would see the threshold rate set at a risk-free rate (say the annual long-term government bond rate) in circumstances where the design of the RRT resulted in no risk of ultimately losing carried forward tax losses. The relevant risk here is not the unique risk of the project itself but the risk of excess deductions being compounded forward not being offset against later positive cash flow from the project (or from other projects) resulting in 'unrecouped' losses. RRT design does not remove the risk of unrecouped losses in the absence of 'delayed full loss offset' via payments equal to unrecouped losses times the tax rate at the end of projects' lives (payments which would result in a design financially equivalence to the Brown Tax). Thus, increasing the RRT threshold rate above a risk-free level might be looked to as a method of offsetting, in a very rough way, the possibility of unrecouped RRT losses and the associated asymmetry imposed on projects' NPV probability distributions.

The interest component on losses carried forward is designed to maintain the value of these deductions so that when sufficient cash flow is available the benefit obtained from these deductions is equivalent (in present value terms) to having full loss offset provisions. Individual investments made in years when sufficient cash flow is available to deduct immediately the full amount of capital expenditures would be subject to the Brown type of tax. The after-tax internal rate of return of these individual investments then would be equal to their before-tax return. By carrying losses forward with a specified interest rate instead of allowing full loss offset, however, the RRT Scheme differs from the Brown Tax Scheme with regard to:

Comparison of RRT and Brown Tax Schemes

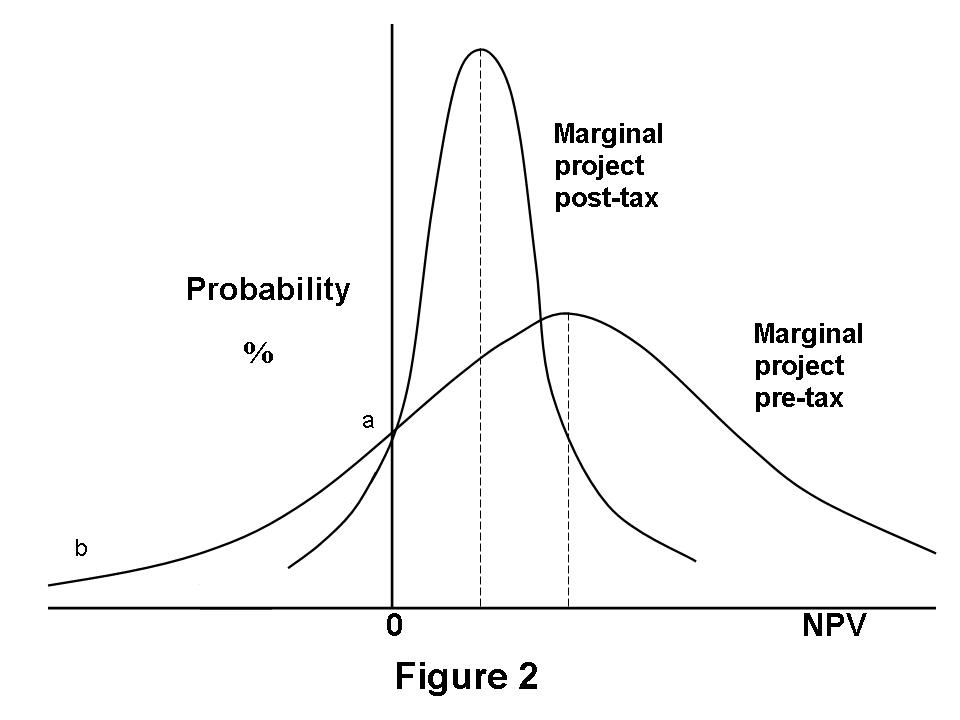

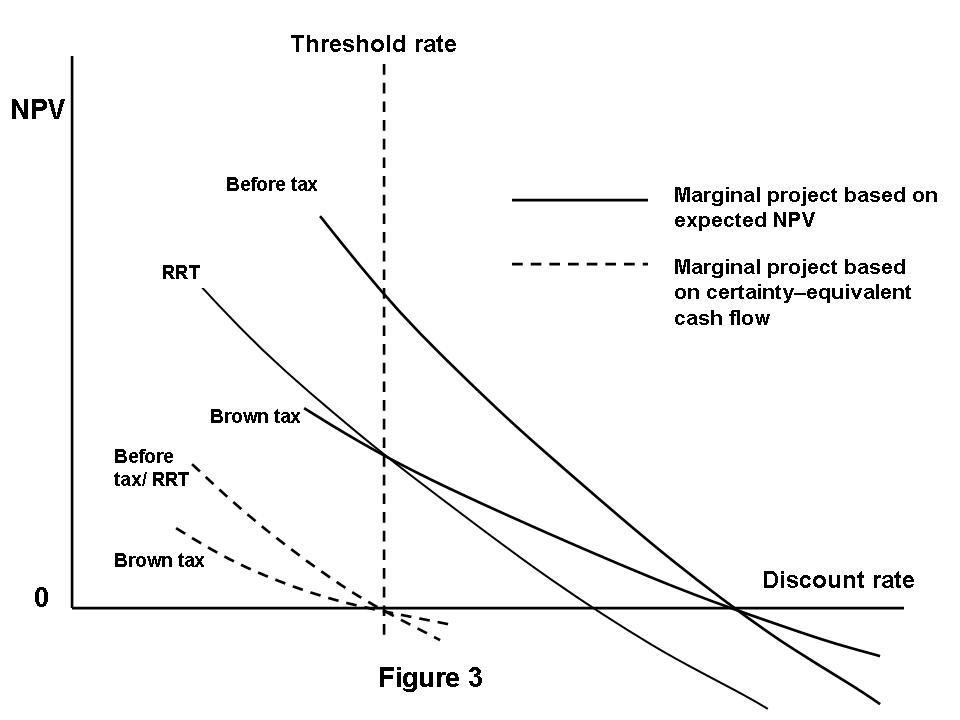

Figure 3 shows comparisons of NPV curves for the no-tax, Brown-Tax and RRT situations for a marginal project determined in two ways: (i) expected NPV determined with RRT threshold rate equal to the risk-free discount rate so that pre-tax NPV and post-tax NPV are positive; and (ii) NPV determined from the certainty-equivalent cash flow of the project with RRT threshold rate equal to the risk-free discount rate so that pre-tax NPV and post-tax NPV are zero (no RRT paid). A 0.5 tax rate applies to both taxation schemes and sufficient income is assumed to be generated to absorb fully the losses carried forward with the RRT Scheme. The results of feasibility studies of a hypothetical oil-field operation shown in Table 1 also highlight the differences between the Brown Tax and RRT Schemes. Although the values in Table 1 were obtained from cash flow analysis, many of the figures in the table could be determined directly from the preceding analysis (reflected in Figure 3) and the values for the no-tax situation. For example (and again assuming no unrecouped RRT losses remain at end of the project's life):

| Taxation Scheme | Internal rate of Return % | NPV of Project (discounted at 10%) $m | NPV of Project (discounted at 15%) $m | Total tax paid $m | PV of Tax Paid (discounted at 10%) $m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. No Tax | 29.5 | 545 | 296 | 0 | 0 |

2. Brown Tax

| 29.5 29.5 | 300(b) 136(e) | 163(b) 74(e) | 792(c) 1320 | 245(d) 409(d) |

3. RRT(f) (.45 tax rate)

| 24.9 27.7 29.5 | 327 420 545(g) | 163(b) 226 296(g) | 664 447 0 | 218 125 0 |

Figure 3 emphasizes the fact that it is only the loss-carry-forward aspect of the RRT Scheme that distinguishes this scheme from the Brown Tax Scheme. For potential projects the extent of the difference between the NPV curves of the RRT and Brown Tax Schemes (the point of intersection remaining fixed) depends on:

Marginal projects based on certainty-equivalent cash flow. Figure 3 illustrates how the difference between the RRT and Brown Tax NPV curves and associated tax payments is maximized with marginal projects when net present values are determined using certainty-equivalent cash flows (or a risk-weighted discount rate, despite the disadvantages of that with mining and petroleum projects) - marginal projects then having an internal rate of return matching the risk-free (or risk-weighted) discount rate, and therefore a zero NPV. Under the RRT Scheme, with threshold rate set equal to the risk-free discount rate, all deductions for capital expenditure must be carried forward and the compounded deductions are only just absorbed fully in the last year of marginal operations. Thus, these projects are projected to pay zero tax. The capital expenditure outlays in the early negative-cash-flow years of the projects are carried forward at the same rate as the discount rate that is applied to the later positive net receipts in the determination of each project's NPV. Thus, only that portion of a project's cash flow (the economic rent) which is greater than the risk-free (or risk-weighted)opportunity cost of investing in the project (the discount rate) is taxed by the RRT Scheme.

In contrast, under the Brown Tax Scheme even marginal operations would pay tax. With this scheme, early reduction in net annual capital outlays through cash rebates is balanced by later higher (than with the RRT Scheme) taxable income. However, if the taxation payments are discounted at the internal rate of return of the project, the present value of the tax paid will be equal to the government cash rebates for tax losses (discounted at the same rate). Therefore, the discounted tax and cash rebates for operations judged marginal on the basis of certainty-equivalent or expected cash flow will also be zero under the Brown Tax Scheme, clarifying and confirming the economic rent taxing characteristic of the Brown Tax Scheme.

To appreciate the economic rent taxing characteristic of the Brown Tax Scheme in practical terms, take an investor with a 15% risk-weighted discount rate (that is, someone requiring a 15% pa return from the expected cash flows of what that investor would consider to be a marginal investment). Say, in the event, that investor does actually earn 15% pa from a particular investment. That investor, looking back at the past stream of government cash rebates and tax payments finds that he has paid no tax. The tax payments associated with the investment (in its later years) just balance the cash rebates (concentrated in the early years of the investment) with discounting at the investor's 15% discount rate. But had the investment earned more than 15% - earning economic rent from the investor's point of view - the investor would then see the government taking out more than it put in.

Under an RRT with a 15% threshold rate, the investor would literally pay no tax on the project with a 15% return and would pay tax on the measure of economic rent defined by the threshold rate should the project earn more than 15% pa. A key difference between the RRT and Brown Tax is highlighted, however, if the investor uses a discount rate of say 10%, below the rate of return of the project and the abitrary 15% threshold rate. Under the RRT the investor would pay no RRT even though to the investor the project was earning economic rent (above the investor’s required 10% return). In contrast, under the Brown Tax, the investor with discounting at 10% would view the project’s tax payments as exceeding the early cash rebates in discounted terms – or the economic rent above the investor’s 10% required return being subject to tax. Economic rent is in the eye of the beholder and the design of the Brown Tax Scheme allows that personal view of economic rent to play out.

Marginal projects based on expected NPV. Using a risk-free discount rate to determine the NPV of each possible cash flow outcome, projects marginal before tax have a positive expected NPV to balance the recognized spread of possible project outcomes - as illustrated in Figure 2. In these circumstances, Figure 3 and Table 1 (taking 15% as the uncharacteristically high risk-free rate for purposes of illustration only) show how the after-RRT rate of return is reduced below the pre-tax rate (29.5%) but is maintained above the threshold rate so long as the threshold rate is less than pre-tax rate of return. In present value terms, the relation between the two schemes depends on the risk-free discount rate used by entrepreneurs who are screening the investment project and the threshold rate applying with the RRT Scheme. As shown in Figure 3, the two taxes result in the same post-tax NPV for any possible positive pre-tax NPV outcome of the project if the discount rate for present value determination is equal to the threshold rate - see, for example, the $163m NPV with discounting at 15% in Table 1 under both taxes applied with a 0.45 tax rate when the RRT threshold rate is the same as the 15% discount rate. The Brown Tax would result in a higher internal rate of return (29.5% versus 24.9% in Table 1), but with intersecting present value curves (as in Figure 3) NPV is the more appropriate measure.

With threshold rate equal to discount rate and no unrecouped losses, therefore, the RRT will reduce a positive pre-tax NPV by a proportion equal to the tax rate - $296m reduced by the 0.45 tax rate to $163m in Table 1 - the same result as equation (4) for a Brown Tax Scheme. Thus, each possible positive pre-tax NPV value in Figure 2 would be reduced by the RRT in proportion to the RRT tax rate, as shown in Figure 2 for the Brown Tax. Moreover, only that portion of the cash flow (the economic rent) of each possible outcome with positive pre-tax NPV which is greater than the risk-free opportunity cost of investing in the project (the discount rate) is taxed by the RRT Scheme. Again, with discounting at the risk-free rate, the present value of the net tax paid by each of these possible project outcomes would be the same under the Brown Tax and the RRT.

Those possible project outcomes in Figure 2 with a negative pre-tax NPV (outcomes along the part of the pre-tax NPV curve marked 'a'-'b') reflect outcomes where unrecouped RRT losses would arise because rate of return achieved is less than the RRT threshold. While each positive pre-tax NPV in Figure 2 would be reduced by the RRT in proportion to the RRT tax rate (absent unrecouped losses), the 'a'-'b' part of pre-tax NPV curve in Figure 2 would not change after the RRT (no RRT paid and no cash rebate received). Moreover, even for pre-tax outcomes with a positive NPV, unrecouped losses under the RRT Scheme would be common (in the absence of delayed full loss offset arrangements), in contrast to the Brown Tax Scheme with its full loss offset provisions. This difference would be particularly relevant, for example, with the mining and petroleum industry where negative cash flows may arise at the closing stages of projects' lives. Thus, in contrast to the neat proportional effect on the NPV of possible outcomes of marginal or above marginal projects under the Brown Tax Scheme (Figure 2), under the RRT Scheme with threshold rate equal to discount (risk-free) rate:

In sum, the Brown Tax reduces each possible pre-tax NPV for all potential projects by a proportion equal to the tax rate. In contrast, even assuming no unrecouped losses are associated with positive net present values and with discounting at the threshold rate, the RRT only reduces positive net present values by this proportion, negative values generally not being affected. Therefore, whereas the Brown Tax has a symmetrical effect on the NPV probability distribution of a project, the RRT will skew this distribution negatively and reduce expected NPV by more than the tax rate proportion. Consequently, the RRT threshold rate is not independent of the RRT tax rate. Nevertheless, the effect of the RRT would not markedly depend on the characteristics of individual projects. With an appropriate increase in the threshold rate above the risk-free rate there may be no marked effect on the screening of potential projects. Varying forms of delayed full loss offset provisions would further reduce these effects.

RRT and Brown Tax in Presence of Income Taxation

Because the investment-neutrality properties of either the RRT or Brown Tax do not impose or require post-tax changes to discount rates (in contrast to income taxation), these taxes are ideally suited as royalties to be applied in addition to generally-applicable income taxation to individual projects or industry sectors. Either the RRT (absent unrecouped losses) or the Brown Tax applied as an extra tax or 'royalty' before or after income taxation, would reduce positive before-royalty NPV outcomes in proportion to the royalty rate independent of the characteristics of particular projects. In contrast to the Brown Tax, under the RRT unrecouped RRT losses would mean negative before-royalty NPV outcomes would generally not change and positive NPV outcomes may be reduced by more than the tax rate proportion. Nevertheless, with appropriate RRT threshold rate selection, regardless of any non-neutral effects of the income-tax system, these theoretical royalty schemes would not further markedly affect marginal screening decisions.

The application of such royalty schemes to an individual industry may cause an entrepreneur to rank a potentially viable project in this industry below a project previously ranked equal in an industry not subject to the royalty. Nevertheless, the lower expected NPV of the project subject to the royalty would be balanced by a lower spread of possible outcomes. A project judged marginal before the royalty scheme because of a zero NPV based on certainty-equivalent cash flow using a risk-free discount rate would remain marginal after the royalty, with unchanged zero NPV. The project would therefore still be screened by someone (assuming healthy mobility of capital) as a viable project. Further, these royalties should not affect the ranking of projects within the industry subject to the royalty (again assuming linear risk functions when assessing the risk/return tradeoff).

Regardless of whether the royalty schemes were applied before or after income tax, specification of annual gross revenue less operating costs (including income tax payments with royalties applied after income tax) in projects' cash flows for royalty purposes - represented by the discounted net receipts variable, R, in the equations in this paper - would correspond with standard income taxation provisions (except for any interest payments or receipts on borrowing and lending). All capital outlays (other than those relating to funding arrangements) in the royalty cash flows - represented by the discounted capital expenditure variable, C, in the equations in this paper - would, however, differ from the income tax treatment of much of that expenditure by being immediately deductible.

RRT and Brown Tax before income tax. With these neutral royalty schemes applied before income tax (and assuming no unrecouped RRT losses), the proportional reduction of before-royalty NPV outcomes - just the positive outcomes with an RRT - is as shown in equation (4). The threshold rate for the RRT would be set on the basis of discount rates before income tax and before (and after) royalty. Royalty payments would be deductible for income tax purposes (and cash rebates under the Brown Tax assessable).

When reporting on pricing in the crude oil industry the Industries Assistance Commission (IAC, 1976) suggested an RRT scheme applied before income tax with RRT payments deductible for income tax purposes. In this case, the excess of deductible expenditure (capital expenditure, operating costs and regional government royalties) over total revenue in each year would be carried forward with interest. RRT would be levied at the specified rate when total revenue exceeded the amount carried forward plus any deductible expenditure in that year. RRT so levied would be then deductible for income tax purposes.

RRT and Brown Tax after income tax. With these neutral royalty schemes applied after income tax (again assuming no unrecouped RRT losses), it is the before-royalty (but after-income-tax) NPV of a project's possible outcomes that would be reduced by a proportion equal to the royalty rate (just the positive outcomes with an RRT). The (unchanged) discount rate - and associated RRT threshold rate - before and after the royalty would be set on the basis of post-income-tax rates of return and discount rates. A NPV outcome of a potential project with one of these neutral royalty schemes (with an RRT, for positive outcomes with no unrecouped losses) applied after income taxation may be presented as:

Garnaut and Clunies Ross (1975) indicated that the RRT Scheme could be implemented in conjunction with an income system. In this case, Garnaut and Clunies Ross suggested that the scheme would be applied after income tax and Garnaut and Clunies Ross (1979) referred to the issue of whether or not credits for RRT would be allowed against home country income tax of foreign investors. Applying an RRT after income tax would require annual after-income-tax negative cash flows to be carried forward with an added interest component (at a specified threshold rate) to be deducted from the future after-income-tax positive cash flows. It would also involve what would often be a difficult task of determining that part of the overall income taxation payable by an investor that is attributable to the operations of the investor subject to the RRT.

Changing an across-the-board income tax rate applying to all industries would change after-income-tax discount rates used to screen investment decisions. This would, in turn, require the threshold rate for an RRT scheme applying after income tax to be adjusted accordingly.

Advantages of RRT and Brown Tax over existing royalties. Given the existing income taxation system in Australia, if additional royalty revenue was sought from some industries without adversely affecting investment screening in these industries, a royalty scheme in the form of an RRT Scheme or a Brown Tax Scheme would be preferable in terms of economic efficiency to other forms of royalties currently used in Australia - such as unit and ad valorem royalties. While providing reliable revenue flows, such existing royalties do not depend on annual project cash flows and are therefore not sensitive to the profitability or otherwise of projects. The existing royalty arrangements can therefore heavily tax marginal projects making them unviable. More specifically, existing royalties both reduce possible positive NPV outcomes and increase the absolute value of possible negative NPV outcomes of potential projects in an arbitrary and ad hoc fashion depending on the individual characteristics of each project. Thus, those royalties tend to skew the before-royalty NPV frequency distribution negatively reducing expected net present values (and rates of return) by arbitrary amounts which depend on the characteristics of each project. Similarly, a marginal project's zero before-royalty NPV based on certainty-equivalent cash flow and using a risk-free discount rate becomes negative after these royalties. Reduced investment opportunities, and arbitrarily changed ranking of potential projects, in the corresponding industry is the result.

Table 2 illustrates the adverse effects which a $2 per barrel royalty could have on investment decisions in the petroleum industry. For illustrative purposes only, again an uncharacteristically high rate of 15 per cent is taken as the risk-free post-income-tax discount rate and the NPV (and internal rate of return) of the projects are assumed to be determined on the basis of certainty-equivalent project cash flows. A 15% rate of return after all government imposts is therefore required for a project to be screened as potentially viable. Table 2 shows that some projects which would have been undertaken before the unit royalty would be discouraged by this royalty. Of the three hypothetical projects in Table 2, only the 400m barrel project would go ahead and then only just (with a 15.9% return after all taxes and royalties). The 250m barrel project would not, with its pre-unit royalty return of 15.3% reduced to 11.4% by the unit royalty. The return of the slightly sub-marginal 200m barrel project (14.3% before any additional unit royalty or RRT) is reduced dramatically to 6.4% by the unit royalty.

| Taxation Scheme | 200m bbl | 250m bbl | 400m bbl |

|---|---|---|---|

| After-Income-Tax Rent Royalty 15% threshold NPV Government take Internal rate of return | -8.1 219 14.3% | 1.7 227 15.1% | 55 634 17.6% |

| After-Income-Tax Rent Royalty 20% threshold NPV Government take Internal rate of return | -8.1 219 14.3% | 3.4 222 15.3% | 110 527 19.5% |

| Before-Income-Tax Rent Royalty 20% threshold NPV Government take Internal rate of return | -14.5 230 13.6% | -0.4 274 14.9% | 46 648 17.3% |

| Before-Income-Tax Rent Royalty 25% threshold NPV Government take Internal rate of return | -8.1 219 14.3% | 3.4 222 15.3% | 97 556 19.2% |

| $2 per barrel royalty NPV Government take Internal rate of return | -85.0 325 6.4% | 43.0 295 11.4% | 20.7 670 15.9% |

In contrast, an RRT (applied either after or before company tax but with appropriately different threshold rates) should have little or no effect on exploration and development decisions. The 400m barrel project shows returns after all government imposts well in excess of the 15% required return with some settings of threshold rate producing a similar government take to the unit royalty (15% threshold with RRT after income tax and 20% threshold with RRT before income tax). The 250m barrel and 200m barrel projects, marginal and sub-marginal before the additional royalty, remains so after RRT. However, the 20% threshold on the RRT before income tax extracts somewhat excessive royalty payments from these smaller projects, the return after all government imposts of the 250m barrel project, for example, falling to just below the 15% required return (with an RRT applied before income tax, the threshold rate determines the before-income-tax return of projects below which no RRT will be paid, not projects' post-income-tax return).

Broad RRT implementation issues. The Brown Tax applied as a royalty scheme would require cash rebates when royalty losses were realized. Therefore, despite practical problems associated with unrecouped losses and, in consequence of that, with selecting an appropriate threshold rate for loss carry forward, a royalty system based on the RRT Scheme may be the variant preferred by governments. Nevertheless, investment could be reduced in an industry subject to the RRT type royalty and ranking of projects within the industry could also be affected by the negative skewing of projects' NPV frequency distributions by this type of royalty. However, unlike existing royalty schemes, the RRT type of royalty would generally skew the NPV probability distribution in a predictable way:

If the RRT royalty were applied on a company basis rather than a project basis the importance of both unrecouped losses and associated adjustments to the threshold rate would be reduced. For a large highly profitable company loss carry forward might only be required on the company's first operation subject to the royalty. This operation might produce sufficient royalty cash flow to offset fully and immediately losses on the company's subsequent RRT-relevant projects. The RRT royalty would then operate as a Brown Tax with these projects. However, small companies would be relatively disadvantaged by a company-based scheme.

Whether operating on a project or company basis, if the associated company had other activities not subject to the royalty, avoidance of royalty payments through profit manipulation would remain perhaps the most difficult practical problem associated with such a scheme. More generally, profit-based royalties are more prone to avoidance activities than simple unit or ad valorem royalties.

Royalty schemes currently used in Australia to raise revenue in the mining and petroleum industries skew the NPV probability distribution of potential projects negatively by an amount which depends on the individual project characteristics, arbitrarily making some prospective investments unviable and changing the ranking of others. In contrast, a royalty scheme in the form of a Brown Tax applied to marginal projects either before or after company tax would have a symmetrical effect on the NPV probability distribution. This effect is independent of the characteristics of the individual project and depends only on the royalty rate. This Brown Rent royalty then would have little effect on the screening of marginal projects and on the ranking of projects above the margin.

On neutrality grounds then, the Brown Rent royalty, applied either before or after income taxation, is preferable to the royalty schemes currently used in Australia. Such a royalty would however see government providing cash rebates equal to annual losses for royalty purposes times the royalty rate.

Investment screening decisions would not be affected by the substitution of a Resource Rent Tax type of royalty for the ideal Brown Tax type provided that, (i) sufficient income is generated (or is available) to deduct fully losses for royalty purposes being carried forward with interest, and (ii) the threshold rate for interest determination corresponds to a risk-free discount rate (recognizing that the losses will eventually be deducted in full). Basing the Resource Rent royalty on a company basis rather than a project basis would minimize the possibility of unrecouped losses and reduce the importance of the threshold rate for loss carry forward under this scheme. However, small less-profitable companies would be relatively disadvantaged by a company-based scheme.

The inevitability of unrecouped losses with a project-based scheme means that a Resource Rent royalty also skews the NPV probability distribution negatively making the threshold rate and royalty rate inter-dependent. However, in contrast to the existing royalty schemes, the Resource Rent royalty would generally affect the NPV distribution in a predictable way. Therefore, with appropriate threshold and royalty rates - say, threshold rate increased above the risk-free rate with the same or reduced tax rate - a project-based Resource Rent royalty would not affect investment-screening decisions markedly and would be preferable to existing royalty schemes.

Brown, E. C. (1948), 'Business-Income Taxation and Investment Incentives', in Income, Employment and Public Policy, Essays in Honor of Alvin H. Hansen, Norton, New York.

Garnaut, R. and Clunies Ross, A. (1975), 'Uncertainty, Risk Aversion and the Taxing of Natural Resources Projects', Economic Journal, 85, June, 272-87.

Garnaut, R. and Clunies Ross, A. (1979), 'The Neutrality of the Resource Rent Tax', Economic Record, 55, September, 193-201.

Industries Assistance Commission (1976), Crude Oil Pricing, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, September.

Musgrave, R. A. (1959), The Theory of Public Finance, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Sumner, M. T. (1975), 'Neutrality of Corporate Taxation or On Not Accounting for Inflation', The Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, 4, December, 353-61.

Swan, P. L. (1976), 'Income, Taxes, Profit Taxes and Neutrality of Optimizing Decisions', Economic Record, 52, June, 166-81.

© Copyright Wayne Mayo September 2013